Some years back, a man wandered into Aaron Deter-Wolf’s office in Nashville, at the Tennessee Division of Archaeology, to hand over a two-foot portion of a mastodon tusk. The man had spotted the relic poking out of a riverbank and sawed off the exposed end. Removing the tusk sullied its scientific value, so Deter-Wolf started trotting it out during talks at grade schools—until a kid dropped it and its outer layers shattered.

For many archaeologists, that might have marked the end of the tusk’s usefulness, but not for Deter-Wolf. He salvaged a few shards and later transformed them into tattoo needles, carving each with flint and smoothing it on sandstone. But when he tried tattooing a colleague with one, it went poorly. Microfractures in the ivory snagged skin each time he withdrew the tip. It was, he recalls, “a bloody mess.”

By day, Deter-Wolf surveys sites to assess the archaeological impacts of new construction. But in his spare hours, he’s among the foremost experts on ancient tattooing, a field formerly discounted but increasingly recognized as offering vital insight into cultures worldwide. Once an outlier, he’s now part of an emerging cohort of researchers showing the practice was more widespread than archaeologists ever knew—and helping reveal new meaning in a historically suppressed art.

(What Maui’s tattoos in ‘Moana’ say about Polynesia’s tattoo culture.)

Hostility to tattoo research has colonialist roots, with missionaries and officials having considered the practice barbaric. As archaeology emerged as a discipline in the 19th century, its practitioners seemed to inherit this disdain, mentioning tattoos in their work rarely and pejoratively, a practice of so-called savages and deviants. And as Deter-Wolf learned early in his career, that attitude lingered into the 21st century.

Now 49, he started as a Mayanist before switching focus to the precolonial southeastern United States. But a personal fondness for tattoos (he has a dozen) drove his side research. After he organized his first conference session on ancient tattooing, in 2009, an older attendee buttonholed him. “The guy told me, ‘There are more tattoos of ancient art on graduate students than there ever were tattoos in the ancient world,’ ” Deter-Wolf says. “He was 100 percent wrong, and it’s not like the evidence was hidden. He just didn’t care to engage with it.”

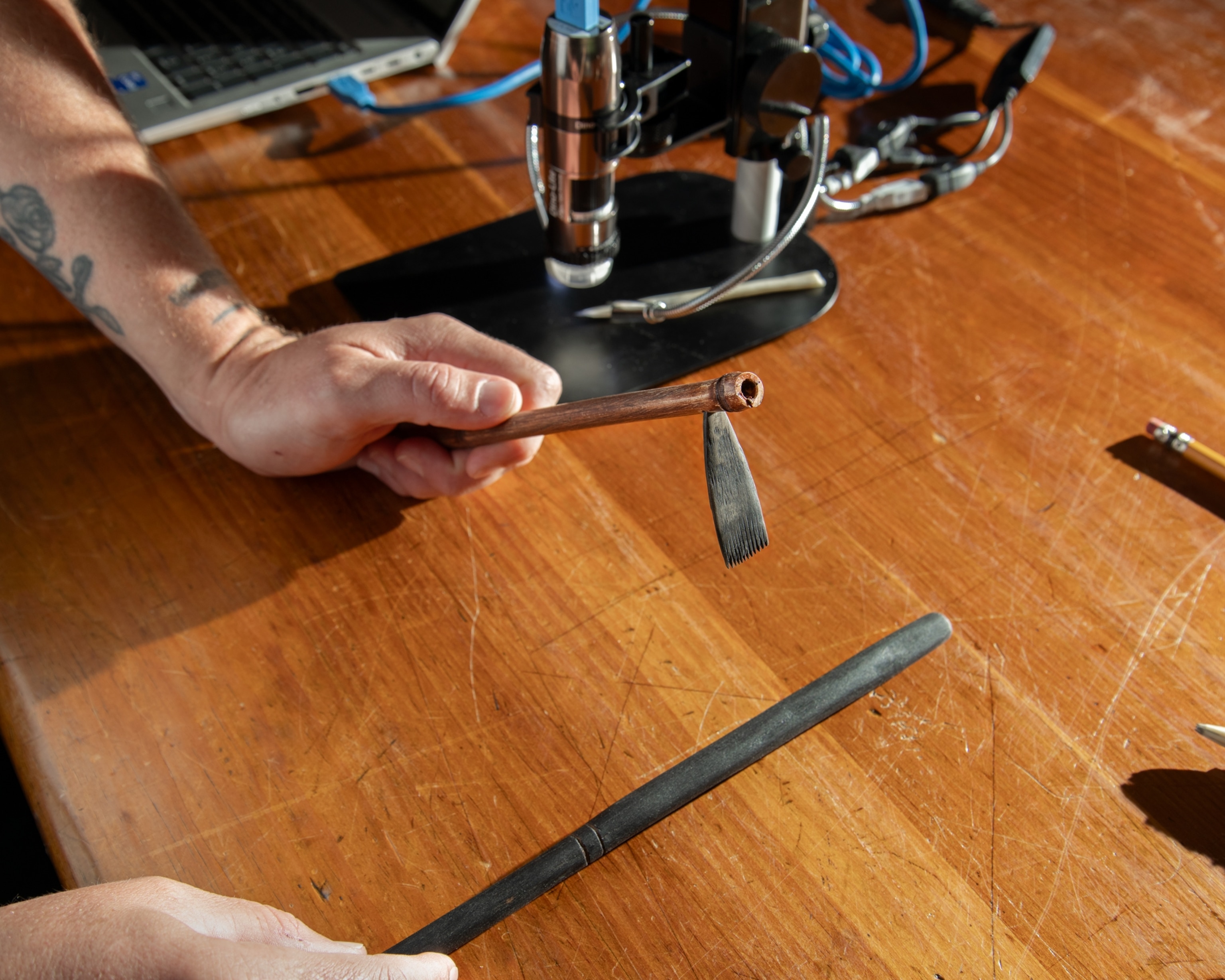

To determine what tools ancient tattooists may have used, Deter-Wolf has made replicas from various materials and tested them—as here, on a slab of pork belly.

Triangles down Deter-Wolf’s arm were tattooed using a mallet and a needle comb, a Polynesian method known as hand-tapping. Two of the bars on his wrist were made as part of an experiment to test deer-bone awls as tattoo needles.

And that lack of engagement, Deter-Wolf says, has led archaeologists to overlook critical details about those they’re striving to understand, as tattoos throughout history have helped define group identity, marked rites of passage, signaled spiritual power.

One way to combat colleagues’ dismissive stance: Deter-Wolf went looking for how best to identify tattoo tools in the archaeological record. Doing so is tricky, since a pointy instrument from a dig site might have been used to apply ink to skin—or it might have been an awl or a sewing needle. How to tell the difference?

(2,000-year-old tattoo needle identified by archaeologists.)

Deter-Wolf started by assembling other archaeologists and researchers who shared his interest, and together they launched a series of experiments carried out over the better part of a decade—some formal and controlled, others more ad hoc. For each, he made tattoo needles out of materials that ancient cultures may have used: feather shafts, deer bones, fish teeth, cactus thorns. And, yes, mastodon tusk shards. They applied either modern tattoo ink or a mix of charcoal soot and water, what most ancient cultures would likely have used. Then he tried the tools out on volunteers and on pigskin—as well as on his own skin.

The feather proved too soft—like tattooing with a Sharpie, Deter-Wolf says (he suspects a historical account that mentions tattooing with feathers was mistaken). The tusk was a debacle. But thorn and bone tools worked nicely; the porous structure of bone held ink particularly well. And when Deter-Wolf and his team analyzed some of the tools microscopically, they noted distinct patterns of wear: Tattooing blunted and smoothed the tips and drove in tiny charcoal fragments. Today the published findings help archaeologists distinguish what is and isn’t an ancient tattoo needle.

After trying out tattoo tools, like this bone of a white-tailed deer, Deter-Wolf compares their wear patterns with those of objects from archaeological sites.

Prickly pear cactus spines were a tattoo tool of ancestral Puebloans in what’s now the American Southwest.

Tattoo needles made from bundled citrus thorns have a history of use in the Pacific Islands and elsewhere.

Among the tools in Deter-Wolf’s office is a replica of a historical Marquesan needle comb, from Polynesia, which is used with a mallet in the process called hand-tapping.

But some insight into millennia-old methods can only be gleaned from ancient bodies. Enter Ötzi, the 5,300-year-old Iceman discovered in the Alps in 1991. Researchers analyzing the 61 lines and crosses spread across his body initially suggested Ötzi’s tattoos were applied by slicing his skin with sharp stones, then rubbing soot into the wounds. Decades later, Deter-Wolf designed an experiment that would allow him to test that theory, collaborating with Maya Sialuk Koch Madsen, a traditional Inuit tattoo artist from Greenland, and Daniel Riday, a tattoo artist then based in New Zealand.

(Ötzi the Iceman: What we know 3 decades after his discovery.)

You May Also Like

Using eight techniques, including poking with a needle and the slice-and-rub method, Riday gave himself eight identical tattoos of stacked triangles on his left thigh. He noted how long each took to heal, along with how much pain he felt. The work took a grueling 12 hours, though time and pain weren’t equally distributed. Some methods took minutes. One Inuit technique, executed with Koch Madsen’s guidance, involved “sewing” his skin with ink-soaked thread and lasted three agonizing hours. Afterward, Riday says, his thigh looked like Swiss cheese.

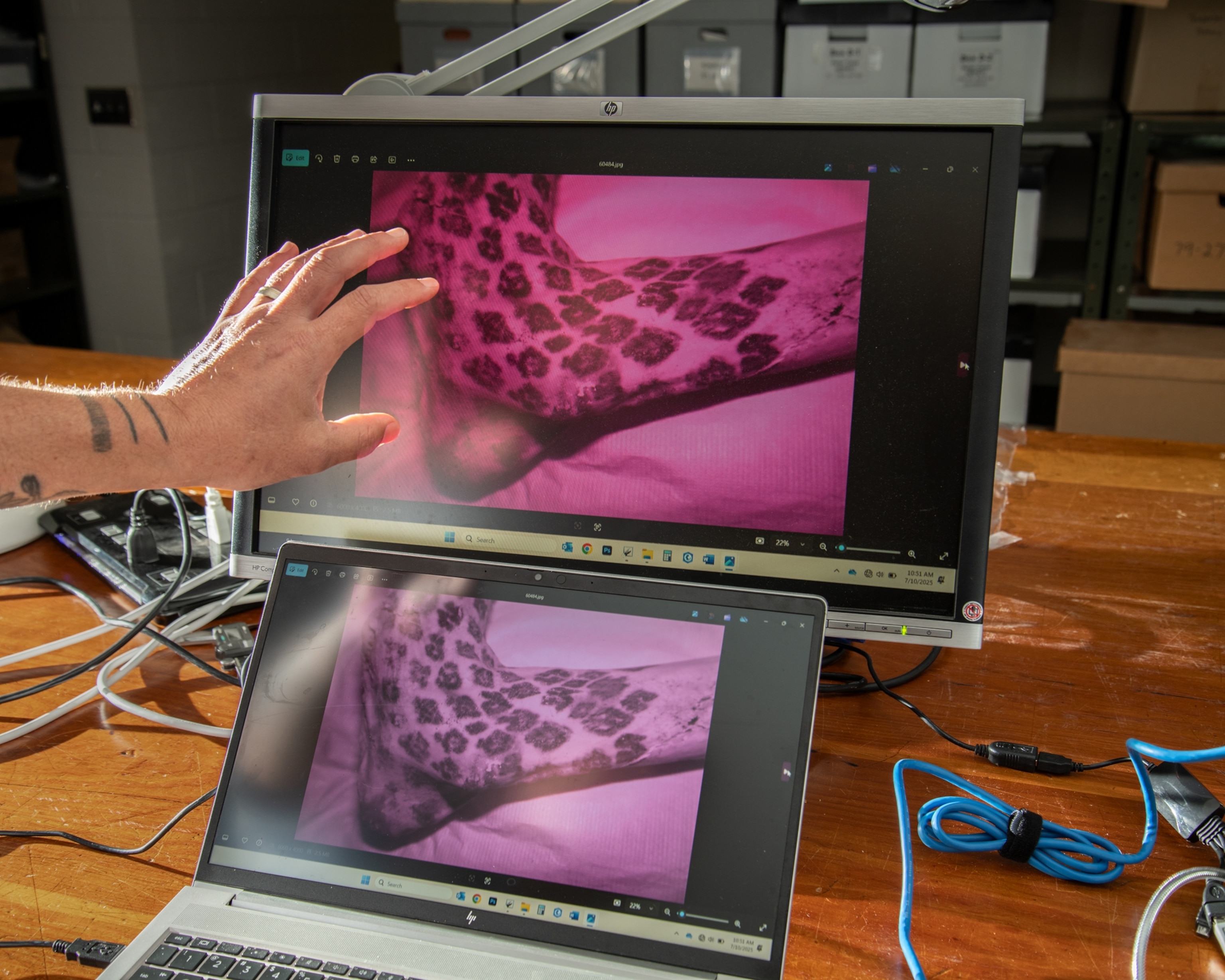

Deter-Wolf later compared magnified images of Ötzi’s tattoos with Riday’s. On the latter, he saw line segments for the slice-and-rub tattoos tapering into wisps. On the needle-poked ones, the segments had blunt, rounded ends that matched Ötzi’s. The Iceman’s tattoos, Deter-Wolf concluded, were not sliced in but carefully stippled with needles. The study shed light on Ötzi’s culture and provided the first published reference set of what differing tattoo applications look like microscopically, now used by archaeologists to analyze tattoos on other mummies.

(Scientists reconstruct the tattoos of a 2,000-year-old Siberian ice mummy.)

Tattoos on mummies, like this one from pre-Inca coastal Peru, can be difficult to see on weathered skin but revealed using infrared photography.

Anne Austin, a co-author of Deter-Wolf’s and an Egyptologist at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, says tattoos can convey details about societies that aren’t found elsewhere. “The things you write down on skin,” she says, “are different than things you write down on paper.” Egyptian texts, for example, have little to say about the role of women in the clergy. But Austin, who has found some of the most extensive evidence of tattooing on Egyptian mummies, has studied a mummified Egyptian woman whose 30-plus tattoos—of hieroglyphs, musical instruments, snake deities, and more—indicate she was something like a priestess. Tattoos over the mummy’s voice box, Austin says, suggest she had an active speaking or singing role, her voice imbued with sacred power.

To coax new information out of old mummies and tools, tattoo archaeologists are increasingly turning to imaging technology. Deter-Wolf and a Canadian colleague, Benoît Robitaille, recently used infrared-sensitive cameras to find hidden ink among one of the world’s largest collections of mummies, from coastal Peru. Some specimens date back 2,400 years, their tattoos obscured by the darkening and weathering of skin over time. The pair are finding, Robitaille says, that religious iconography in tattoos stayed consistent over almost two millennia, suggesting the local beliefs persevered even during periods of invasion and conflict.

Archaeologists make composite drawings to show in more detail what can be harder to see on photos of an ancient body. Researcher Benoît Robitaille rendered these designs that he and Deter-Wolf found, using infrared photography, on mummies from the Peruvian coast.

Illustration by Benoît Robitaille

The frontiers of the discipline likely involve applying such modern techniques to more museum collections. And as a new generation of tattoo-savvy scholars are reassessing what lies in tombs and sarcophagi, they’re also belatedly recognizing and collaborating with Indigenous stewards of ancestral tattooing techniques. “As Indigenous people, we’ve kind of been taught that there were people before, and then there’s us,” Koch Madsen says. “This science is building a bridge between the two, so we can feel connected to our ancestors again.”

Opportunities for more discovery seem almost limitless, Deter-Wolf says, noting that researchers have found more evidence of tattoos on mummies in the past five years than was documented over the previous 150. “We’ve got this outrageous dataset,” he says. “Now, what are we going to do with it?”

(These sacred tattoos were banned in Okinawa. A new generation is bringing them back.)

A version of this story appears in the November 2025 issue of National Geographic magazine.